Dr. Lynda’s Rule #1

You need to put the targeted behavior in positive terms rather than in negative terms. So applying this to some of the behaviors listed above you might say:

- “Mary will complete her homework within the timeframe allowed”

- “Ted will show positive interaction behaviors when playing with his siblings”

- “Lily will be able to sleep in her own bed throughout the night”

- “Chandler will use his control behaviors when frustrated”

- “Samantha will complete age-appropriate tasks without parent involvement”

You need to go through this step – it is extremely important to phrase what you want to see in a very positive way for your child.

Dr. Lynda’s Rule # 2

Once you have decided on the targeted behavior and phrased it in a positive way, have a meeting with your child to explain this new way you’re going to do things. We are going to use a reinforcement system that most children “love”. Rule #2 emphasizes that your child must understand completely what the behavior of concern is so that she can recognize it when it happens. Recognizing the behavior is essential for the student to change it. Spend time discussing the behavior of concern, even role-playing, so that everyone is well aware of what you’re working on.

Dr. Lynda’s Rule #3

Boy, this one is very important! Discuss with your child what you would like to see instead of the behavior of concern. Children and even teenagers need to know explicitly what you are looking for – what you expect. It needs to be specific and easily understood. Some of the targeted behaviors speak for themselves, e.g. “Lily will be able to sleep in her own bed throughout the night”. But others are more detailed and require more work.

Let’s take, for example, “Ted will show positive interaction behaviors when playing with his siblings”. Ted has no idea what positive interaction behaviors are and so we must teach him, and show him what the expectation would be. Again, some modeling and role-playing might be helpful. Keep it simple. Come up with a few positive interaction behaviors that you can write down and talk about so that Ted knows exactly what should happen when he is doing something with his siblings. Of course, this could be introduced to all the siblings at the same time. We may decide that these positive interaction behaviors are:

Keeping voice level down (go through three different voice levels such as whispering giving it a # 1, normal inside voice #2, shouting #3.) By doing this you can use a simple technique such as raising fingers to indicate that the voice level is too much.

Sharing materials and playing fair in games – go through examples of what this means and what you expect to see; you may discuss being polite, making sure everyone has their turn; refraining from grabbing things from others

Keeping language pleasant – talk about words that would be inappropriate, ways to thank someone for their help, how to express concern about something that happened

Dr. Lynda’s Rule # 4

Especially with elementary age students, it is often helpful for the student to externalize the behavior of concern so that he would see himself in a game or competition to beat the opponent. He should name the opponent, perhaps choosing a comic character. In this way the behavior becomes more concrete and is less likely to be internalized as something “bad” about himself. He will be fighting against the opponent – trying to win the competition. He may also want to draw the character and write down the negative behaviors this opponent that he is fighting against exhibits. Help him with this.

Fighting an opponent is a great strategy not only for more external behaviors but also for behaviors such as anxiety. Knowing what you are fighting against and developing strategies to win against that opponent can be extremely helpful in reducing anxiety.

Dr. Lynda’s Rule # 5

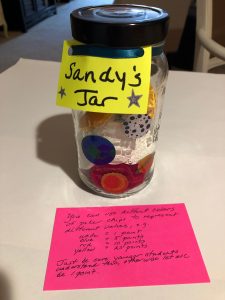

For many situations, it is important to put into place some techniques to take into account the particular situation presented by the child. Let’s take as an example, “Lily will sleep in her own bed through the night”. In a case such as this, it is important to put into place some calming rituals that are done consistently with bedtime. The parent reading a book, the use of night lights or calming lights systems, drinking milk and a cookie, having a pet sleep in her room or have a special stuffed animal, etc. It will also be important that when the reinforcement menu is constructed that it includes lots of special time with parents that she earns for her ability to fight her opponent.

For some situations such as “failure to comply with a parent directive” – make sure that you have given the directive directly to the child with eye contact (not yelling from the kitchen). This is especially important for students with ADHD and auditory processing disorders. You can build in some leeway, e.g. if you’re trying to get the student to comply with a directive the first time she hears it, at the beginning you may give more points for complying the first time and fewer points if you have to give one reminder. Just figure out what you need to do for your child.

Students who tend to overreact with frustration need to be taught some specific personal strategies to employ once they can recognize that they are frustrated. It’s a good idea to explore the whole concept of “frustration” with the child, talking about how normal it is with everyone, but that people need to develop their own strategies for dealing with frustration in an appropriate way. You may need to spend some time in having your child recognize frustration, use the actual word, and then develop with her a few strategies that she can use when she feels it (instead of making loud noises, whining or loss of emotional control). You could even put these in a strategy notebook that she illustrates and she can be reinforced for the actual use of her strategies. This should lead to a reduction in negative behaviors.